Some Observations by a Massachusetts Second Amendment Attorney

When the United States Supreme Court handed down New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen in June 2022, it was supposed to mark a reset. A long-overdue correction. The Court made unmistakably clear that the Second Amendment is not a second-class right, and that the modern “balancing tests” invented by lower courts—interest balancing, intermediate scrutiny in disguise, means-end rationalizations—were unconstitutional distractions.

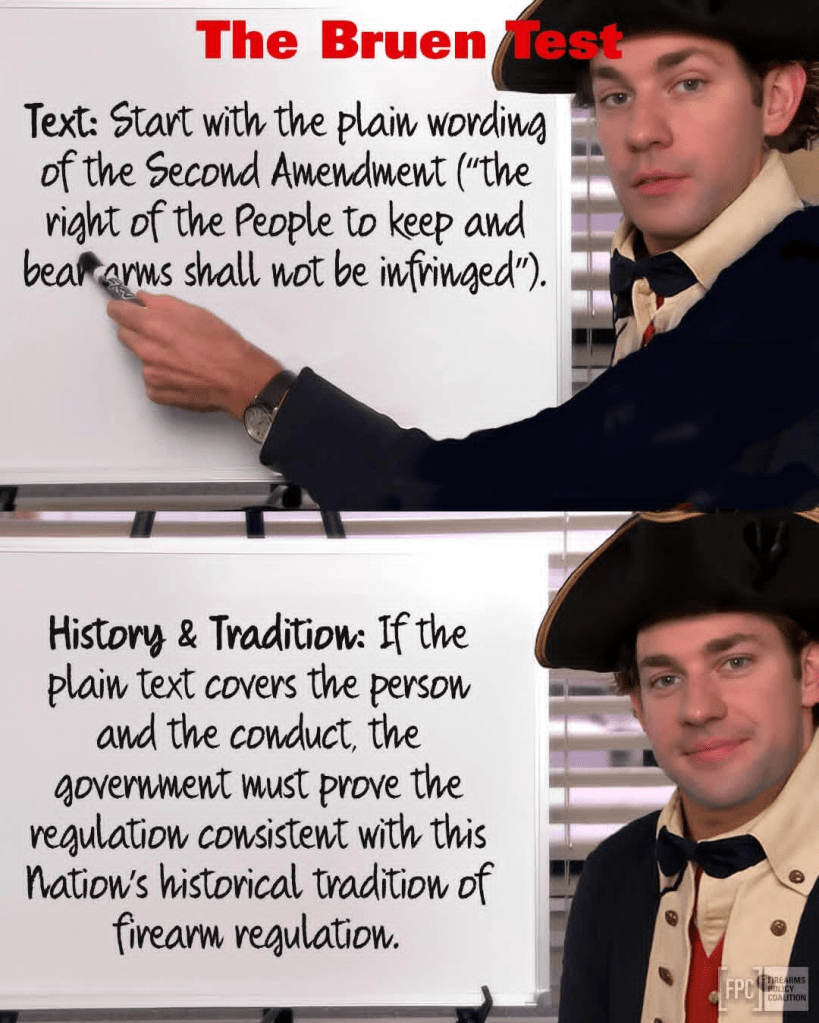

The rule was simple: If the government wants to restrict the right to keep and bear arms, it bears the burden of proving that the restriction is firmly rooted in the text and historical tradition of the Second Amendment.

Not public-safety speculation.

Not modern policy preferences.

Not “we think this is a good idea” judicial activism.

Only text, history, and tradition.

That is the test.

But in Massachusetts—as in many jurisdictions that have long resisted treating the Second Amendment as a real constitutional right—Bruen has been treated less like binding precedent and more like an advisory memo that can be politely (and politically) ignored.

And the evidence of that is mounting.

I. The Massachusetts Courts’ Persistent Misreading of “Suitability”

Massachusetts remains one of the last states clinging to a discretionary licensing regime, using the elastic, amorphous and historically unsupported concept of “suitability” to deny or restrict firearm licenses based on mere suspicion, sealed records, ancient incidents, and grossly subjective hunches about “risk.”

Under Bruen, this entire framework is untenable.

“Suitability” is not a historical analogue.

It is not a “longstanding” disqualifier.

It is not rooted in founding-era tradition.

It is a 20th-century public-policy invention that Massachusetts courts continue to elevate as if it carries constitutional pedigree.

Even after Bruen, trial courts, and even appellate courts, continue to treat “suitability” determinations as if they enjoy quasi-deferential review. They uphold denials where there is no charge, no conviction, no active restraining order, and—critically—no evidence of historical grounding.

Bruen expressly forbids this.

Yet we continue to see:

- Denials based on decades-old sealed records that would not disqualify under any statute.

- Denials based on subjective police conclusions about “attitude,” “concern,” or “potential risk.”

- Judicial language implying that licensing authorities “must have discretion” for public safety—precisely the balancing test Bruen condemned.

Massachusetts courts have effectively revived the very reasoning that the United States Supreme Court said must end.

II. The “Historical Analogues” That Aren’t

Post-Bruen, many courts nationwide have attempted to justify modern gun restrictions by pointing to historically irrelevant examples such as:

- 19th-century surety laws taken wildly out of context. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court did precisely this in its Commonwealth v. Marquis decision of 2025.

- Regulations applying only to concealed carry while ignoring open carry

- Militia inspection rules mislabeled as “gun regulations”

- Colonial-era loyalty oaths that have all of nothing to do with modern licensing

But Massachusetts courts, in particular, treat these out-of-context fragments as if they constitute an unbroken historical foundation supporting broad modern restrictions.

As a Second Amendment attorney, I find the methodology deeply flawed. And, that is the only good thing I can think of to say about it.

If a law was:

- rare,

- geographically isolated,

- short-lived,

- controversial even in its own era, or

- not disarmament in any meaningful sense,

then under Bruen, it cannot support a modern analogue.

But Massachusetts decisions routinely treat isolated examples as if they were universal practices—stretching historical scraps into sweeping justifications for modern licensing discretion, storage mandates, “suitability” findings, and categorical carry prohibitions.

This is not faithful application of Bruen.

It is exercise of personal policy preference dressed in the garb of jurisprudence.

III. “Public Safety” Has Returned Through the Back Door

One of Bruen’s central holdings was that judges are not permitted to create public-safety exceptions that are unsupported by historical tradition.

Yet what we see in Massachusetts (and across the First Circuit) is an unmistakable pattern:

If the regulation sounds “reasonable” to modern ears, courts bend history until it fits.

The judiciary’s institutional instinct is to preserve discretionary state authority, even when the Constitution—and Bruen—require the opposite. So we see lines like:

- “The Commonwealth has a compelling interest in reducing gun violence…”

- “It is reasonable for a licensing authority to err on the side of caution…”

- “Public safety requires deference to police judgment…”

These statements are, in the post-Bruen world, irrelevant.

They are the exact balancing-test reasoning the Supreme Court explicitly forbade.

Yet they keep reappearing in Massachusetts rulings like stubborn weeds.

IV. The Larger Problem: Judicial Culture

The deeper issue is not doctrinal but cultural.

For decades, Massachusetts courts operated in a legal environment where the Second Amendment had practically no force. Licensing chiefs could deny for almost any reason. Now, they can deny or take away your license if they subjectively deem you to be someone who “may pose a public safety risk.”

So much for improvement.

Courts could uphold almost any restriction on the theory that “guns are dangerous.” The judiciary was accustomed to broad state authority and minimal constitutional boundaries.

Bruen flipped that model.

But the judicial culture has not responded accordingly.

In my 28 years as an attorney, I have never seen anything remotely approaching this level of disregard, or at best contortion, of a US Supreme Court precedent.

Many courts simply cannot accept that the Second Amendment now has equal status with the First, Fourth, and Fifth. They are still applying a “trust the police” instinct instead of what is supposed to be the “trust the Constitution” default.

V. Why This Matters

If courts get Bruen wrong, the entire right collapses in practice.

A right that exists only for people who satisfy the unreviewable “comfort level” of a police chief is not a right—it is a privilege.

A right that can be stripped based on sealed records or non-criminal medical incidents is not a right—it is conditional permission.

A right that depends on a judge’s personal views on firearms or public safety is not a right—it is a hope.

The Second Amendment means what the Supreme Court says it means—not what Massachusetts licensing officers, police chiefs, or even judges wish it meant.

VI. What Must Happen Next

To restore constitutional fidelity, courts must begin to:

1. Apply Bruen faithfully—without balancing tests.

Not “Bruen-lite.”

Not “Bruen with safety considerations.”

Actual Bruen.

2. Recognize that discretionary licensing has no historical analogue.

If the government cannot point to a comparable 1791 regulation, the regulation is unconstitutional. Period.

3. Stop relying on sealed records, dismissed charges, and speculation.

These have no historical basis as disqualifiers and violate the presumption of liberty embedded in the Second Amendment.

4. Acknowledge that the burden is on the government, not the citizen.

This is the core shift Bruen demands—and the one Massachusetts courts most resist.

Conclusion: Bruen Was a Beginning, Not a Suggestion

The Supreme Court has spoken:

The Second Amendment is a real constitutional guarantee that the states must respect.

Massachusetts is not doing so—not yet.

But every motion, every appeal, every challenge chips away at the entrenched disdain for this right. The text, history, and tradition test is not a fad. It is the lynchpin of the Constitution’s 2nd Amendment. And over time, even the most reluctant jurisdictions will be brought into alignment.

The courts may resist, but the Second Amendment is patient.

Most importantly, its defenders—my colleagues, citizens, a relative handful of scholars, and the current Supreme Court—are not going away.

Leave a comment