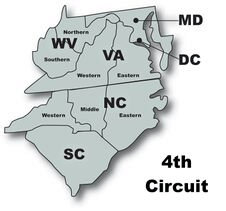

Today, June 18, 2025, the US Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit upheld the federal ban on sales of handguns to 18-21 year-olds.

In an initial victory for gun rights advocates, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia had earlier ruled that the federal statute did violate the Second Amendment. Applying the two-step Bruen test, the court concluded that:

- The plaintiffs’ conduct—purchasing handguns—was protected by the Second Amendment, and

- The government failed to point to an American historical tradition of comparable regulations that would justify the ban.

As a result, the district court granted a sweeping nationwide injunction, prohibiting the ATF from enforcing the law against any 18-to-20-year-olds purchasing handguns from dealers.

Fourth Circuit Reverses on June 18,2025:

“The People” Includes 18–20-Year-Olds

The 4th Circuit panel began by assuming, without dispute, that 18-to-20-year-olds fall within the Second Amendment’s protections and that the commercial purchase of handguns qualifies as “conduct” covered by the Amendment. This wasn’t where the legal battle would be fought. How it is that their access to entire classes of firearms can be outright prohibited, yet they still fall within the ambut of the 2nd Amendment was left unexplained.

Historical Analogues and Bruen’s Demands

The key issue, instead, was whether the government could demonstrate that the restriction aligns with “this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation,” as required by Bruen.

The Fourth Circuit said yes.

Relying on a body of early state laws, colonial-era practices, and the legal doctrine of infancy (which treated those under 21 as legal minors), the court held that there was a historical basis for distinguishing between adults and young people in the regulation of firearms. In particular:

- Several 19th-century states enacted laws restricting the sale or possession of pistols to minors (often defined as under 21).

- The legal concept of “infancy” historically allowed the government to impose additional limitations on young people’s rights and conduct—even if they had reached 18.

The court emphasized that the Bruen test does not require the government to identify a historically identical law, but only a “relevantly similar” one that reflects the same principles.

Thus, the court concluded that § 922(b)(1) met the constitutional standard under Bruen and was a valid exercise of federal authority.

I suspect that this decision illustrates that the concept of “relevantly similar” is going to be interpreted extremely expansively by many courts in the coming months.

U.S. Circuit Judge Marvin Quattlebaum dissented from the two-judge majority. Quattlebaum reasoned that the doctrine is not an appropriate analogy because, while the doctrine burdens the rights of sellers, the 1968 Act burdens the rights of purchasers. Quattlebaum wrote that the doctrine serves a paternalistic interest while the prohibition serves a public safety interest.

“I recognize that to many, banning sales of handguns to those under 21 makes good sense. I appreciate that sentiment, especially during a time when gun violence is a problem in our country,” the Donald Trump appointee wrote. “But that is a policy argument. As judges, we interpret law rather than make policy.”

Indeed.

Leave a comment