I chuckled when I’d first heard last year that the legislature was about to amend the Massachusetts “Red Flag Law.” Why would I laugh at yet another infringement on this right in the birthplace of American liberty?

As anyone seeking to exercise this right is acutely aware, Massachusetts maintains a myriad of gun laws that run counter to this right. Two primary legal mechanisms allow for the removal or suspension of firearms access: the Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) statute—commonly known as the Red Flag Law—and the licensing suspension and revocation process under M.G.L. c. 140, § 131, which governs the issuance and regulation of License to Carry Firearms (LTCs) and Firearms Identification Cards (FID’s). While both mechanisms can restrict, or effectively eradicate, a person’s access to firearms, they differ substantially in terms of purpose, procedure, legal standard, and Due Process.

Overview of Each Law

1. Red Flag Law (ERPO) – M.G.L. c. 140, §§ 131R–131Y

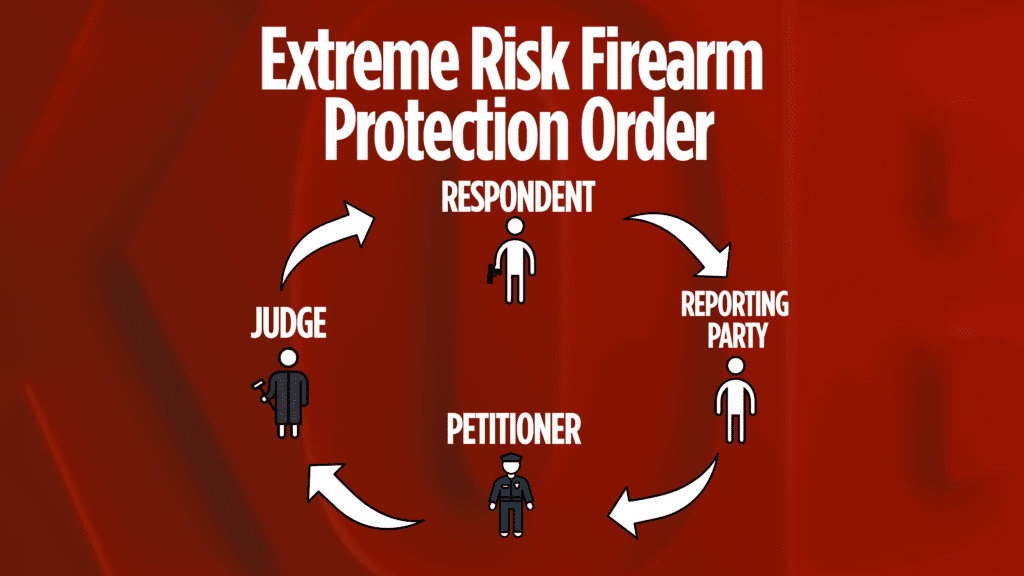

Massachusetts enacted its Red Flag Law in 2018. It authorizes courts to issue Extreme Risk Protection Orders to temporarily remove firearms and suspend the firearms license of individuals who pose a significant danger to themselves or others.

- Petitioners: Family or household members and law enforcement officers may petition. Under the newly approved revisions of 2024, school administrators and licensed health care providers are also allowed to file.

- Legal Standard: The court must find by a preponderance of the evidence that the person poses a risk of causing bodily harm.

- Duration: Emergency ERPOs last up to 10 days; final orders can be issued for up to one year, subject to renewal.

- Court Involvement: All orders are issued by a judge in the District Court.

- Focus: Primarily preventative, focusing on imminent danger related to mental health or violent behavior.

2. Suspension or Revocation under M.G.L. c. 140, § 131

This provision governs the discretionary issuance, suspension, and revocation of LTCs by licensing authorities, typically local police chiefs.

- Issuing Authority: Local Chief of Police has broad, virtually unlimited, discretion, especially regarding “suitability.” The only definition of what makes one “unsuitable” is if, in the subjective belief of the licensing authority (chief of police), the LTC or FID holder “may pose a public safety risk.” This is arguably, everybody (see my Westbrook case discussed in this blog).

- Legal Standard: A license may be suspended or revoked if the holder is found to be unsuitable, meaning they “may” pose a risk to public safety.

- Process: Police chiefs may act without prior notice, but must provide written notice and allow for a post-suspension hearing under Chambers v. Chief of Police of Shelburne.

- Focus: More administrative and ongoing character-based, rather than emergency-based.

- Appeal: Individuals may appeal the suspension to the District Court, but there is no guaranteed timeframe for a hearing and the case law says that the judge is to uphold the chief of police’s decision unless he or she “abused his discretion” or acted “arbitrarily and capriciously.”

Even a cursory comparison, such as above, leads to a couple of inescapable questions:

- Given that under existing Massachusetts law (which is of highly-dubious validity under the US Supreme Court Bruen precedent), the chief of police has virtually unbridled discretion to immediately and unilaterally take away the license (and the firearms) of a Massachusetts resident, what “need” was there to have the Massachusetts red flag (ERPO) law to begin with?

- Why would a chief of police even bother to go the route of filing a red flag law given that their discretion to instead simply suspend is almost unbridled, and is limited in duration only by their own subjective whim?

Question 2 is undoubtedly why I see so very few red flag (ERPO) petitions being filed.

The suspensions, in contrast, only seem to grow by the day.

Leave a comment